Here is a simple preparation for leafy greens that will stand you in good stead. It has enabled me to go from someone who was exclusively a salad person to someone who is always up for a savory bowl of greens. We eat them as a main course with bread, or mixed with beans, with or without grated Grana Padano or Parmigiano, or mild aged Pecorino.

This is a basic preparation method which works for all kinds of leafy vegetables, from lettuce, to escarole (my new favorite), to turnip greens (rape), to swiss chard, to kale, to spinach. Of course the first step is to clean the leaves thoroughly. Whether they come from the market or the garden, this involves inspecting the leaves for bugs, slugs and snails. Usually a couple of baths in water will do the trick, then I make a quick trip outside to liberate these hangers-on. They either survive the adventure or end up sacrificed to the chickens, depending on whether or not I feel like playing God today. If you miss some, don’t worry, they will float to the top of the boiling water and you can pick them out, and nobody will be the wiser!

Bring a big pot of water to a boil, enough to cover about half the volume of leaves, and add a generous handful of sea salt. Don’t use the iodized kind or you will taste it, and you will regret it. Stuff all the leaves down into the boiling water, and stand by to shift the mass in the pot while it cooks. Regardless of the variety of greens, you will want to leave them until they are thoroughly wilted. Meanwhile, slice up some garlic, about a clove for each cupful of cooked greens.

At this point, you want to drain the greens, but reserving at least a cup of their water. I dip them out and into a bowl with this extra liquid. Then I throw out the cooking water and use this same pot to saute the garlic in about two tablespoons of good extra virgin olive oil. Fry the garlic in the oil until it begins to skate around in the pan but don’t let it brown!

There are two ways to go at this point: Plan A is for greens with sweet red pepper, to be eaten as is. Plan B is for greens mixed with beans for a hearty one-dish meal.

Plan A: Get your peperoncino ready. Now here is a problem: We use liberal quantities of sweet red pepper powder at our house, but I’m not sure what the American equivalent would be. It is similar to paprika, but if you can find a sweet red pepper powder that is not just generic paprika, you will have the nearest thing to what we use. I suspect maybe a Mexican market might have this? If you can’t find it then I suppose paprika will have to do. Now get ready! At this point you can add your peperoncino, about two tablespoons. Be quick! It will immediately begin to bubble as you stir it in, and you should dump the greens into the pan immediately. Bring the whole pot to a good simmering boil. At this point it is up to individual taste how long you cook it. I usually leave it on the flame long enough to evaporate most of the liquid. Eaten hot with a sprinkling of cheese (my husband, a D.O.C. southern Italian, scoffs at this practice) or at room temperature with a slice or two of good bread, that’s it. Enjoy!

Plan B: Get yourself a couple of cupfuls of cannellini, great northern, even pinto beans, and make sure they are soft. Cook them yourself or use canned, either will do. You want equal amounts of beans and greens. In a pan, saute about three heaping tablespoons of a mixture of finely diced celery, onion, carrot, and garlic in two or three tablespoons of extra virgin olive oil. ( I usually make up a huge batch of this vegetable “soffritto” mixture and freeze it in ice cube trays. Just stick your nose into the freezer bag at any time thereafter for quick culinary inspiration!) Dump the beans with their cooking liquid into this mixture and bring to a simmer. Add a bay leaf and one or two small, peeled and chopped tomatoes. Cook the beans about forty minutes or so and don’t let them stick and burn! Add liquid to keep it soupy if you need to. You are now ready to combine the two mixtures and serve. Add generous grated cheese. I like to add a few drops of really hot oil to my bowl, and a good crusty toasted bread will complete the meal. Call it soup or stew, it is pure comfort food!

paintings: “Another Summer Salad, oil on canvas, 2011

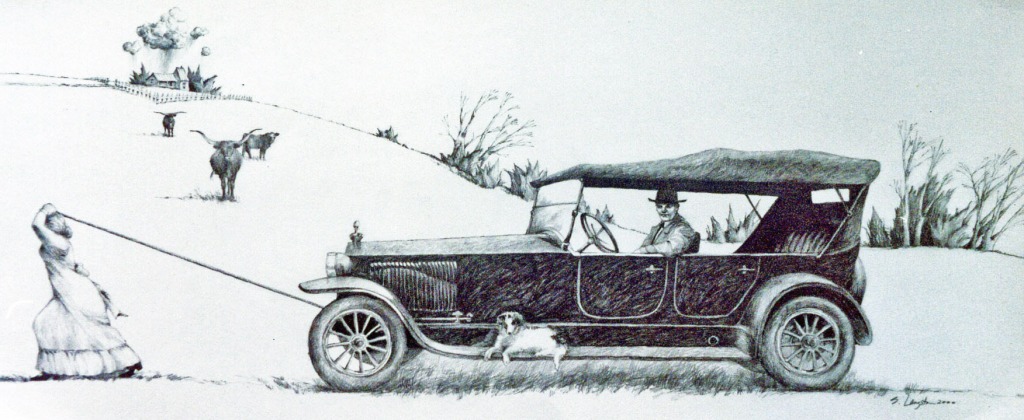

“A Vegetarian Courtship” oil on canvas 2003