I heard a song on the radio tonight, a woman singing about “America,” lamenting its propensity to become ever more unsatisfactory. I cannot disagree with her criticism, yet maybe she is just too close to be able to appreciate its positive nuances. Or maybe there is another song which sings the praises, I don’t know. It made me think about what it means to love a country, an abstract ideal of a place contained within corporeal geographical boundaries.

You might think that I, having abandoned my country, would be less than patriotic. It seemed almost effortless to go elsewhere. Actually I was born in Canada but was thoroughly absorbed into the United States by the age of about eight, whether by indoctrination or simple distraction I don’t know. I do know that when I was born my mother was gnashing her teeth at the snow and darkness, waiting for the day when she could return to a place as close to Oklahoma as her husband’s professional life would allow. I know this necessity was critical because we lived in a motel in Austin for a couple of months until my father could maneuver his way into a job at the University. He arrived confident that he would be indispensable here, and his wife’s urgent need for her “America”, as soon as possible, lit a fire under him.

I think it killed my mother’s soul that I decamped as I did, allowing myself to be absorbed in the form of duffel bags and boxes into the Italian miasma. Surely at first she couldn’t foresee the months stretching into years and decades. She and I had never liked Italy, briefly visited twice in my childhood. There was nothing of value I could see here; just shabby truckloads of tiresome paintings and architecture, broken statuary and annoying men who stared for too long. She was forever a rural Oklahoma girl, who, in her own time, could not wait to get as far away from home as possible. She was always much too diplomatic to tell me how my choices had hurt her. I wonder how her mother, in her time, had thought of her daughter’s own wanderlust and rejection of life on the farm. I am betting that she understood.

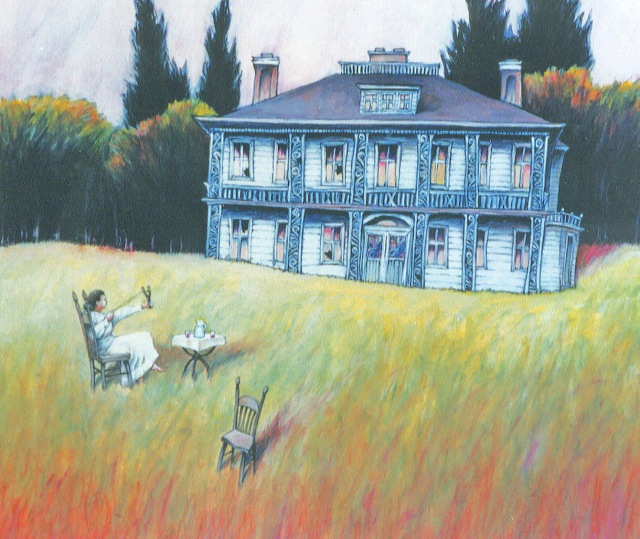

“Home Sweet Home,” mixed media on paper

It is a terrible thing to try and express provincial metaphors which no one shares. Or crack a lame joke which is met with blank stares. Or endeavor to recount a wonderful experience which becomes tedious in the telling, as every nuance must be explained in plodding precision, patiently tolerated by the listeners as long as it does not go on too long. A shared culture is a wonderful thing, do not underestimate its charms!

Imagine telling a story without being allowed to use certain ideographical expressions, or word forms such as pronouns or adjectives. Who was this Jackie Gleason fellow? What do you mean, the five second rule? Why would a person be a potato on a sofa? Why do you insist on using those bucket-sized drinking glasses? A friend once provoked me by saying that I could never really understand a certain Italian singer/songwriter because I lacked the baggage, the cultural knowledge, the historical background. So right he was. Intellectually I can understand the meaning, certainly the musical sounds, but what I hear is unavoidably different, somehow skewed and hollower than the artist intended.

I think that living in a different place, a culture where much cannot be taken for granted until it is internalized, creates a unique appreciation of provenance. Imagine a woman who finds the presence of children irritating up until the day she finds herself unable to contemplate life without her own. Suddenly she understands that her offspring have given her a stable and sustaining anchor, and she is able to love all those other children as well. She knows what they are, is able to empathise with them. Being away from my home has allowed me, as I came to absorb the Italian culture, to appreciate my American-ness. My country has become so much more important to me in its absence because I have been able to distill my ideas of it through a foreign filter. It is almost intoxicating.

So this is how I have come to be a fiercely patriotic person, and while I am forever attached to Italy with many roots, it is the United States of America that I love. Can one really love a country? No, probably not, but I carry around inside me a solid and comforting load of shapes, smells, stories, and conventions that are uniquely my own and are dearer to me than most things. My hope is that my children will also absorb this love and weave a truly wonderful tapestry out of their double load of culture. Wouldn’t it be fantastic if they married members of yet other cultures? I am prepared to travel.

“The Choice” pencil on paper, 28 x 40 inches